IT Automation Starts with Standards

In a previous post (Why Automation?), I gave some reasons for making IT and business operations more automated. That’s great, you say, but how? In this post, we’ll look at a starting point that doesn’t even require software. In fact, it isn’t strictly technical at all and is actually part of effectively running any business.

Special Snowflakes: Nice for Paintings, Bad for Business

Let’s start with an example. Snowflake Financial, a fictitious savings and loan company, relies on their IT department to manage the infrastructure that runs everything from payroll processing to the customer-facing website. Snowflake IT takes pride in providing special attention to every request, with each of the support staff taking a unique approach to performing their tasks.

When a new virtual server is needed, the process varies depending on the person:

- Jim is talkative and encourages everyone to pick up the phone when they need a server. After an informal discussion, he writes a few specifications in his notebook, and tells the caller “gimme a couple days”. First, Jim picks a host machine that seems to have similar servers. He also likes to put similar workloads together on the same storage volume. He clones a template server that he made for himself, and configures it manually according to his notes. When it’s finished, Jim calls the requester back and gives them the access information over the phone. If they’re not available, he leaves a voicemail.

- Connie is shy and prefers email. After getting an initial request, she responds with a Word document containing instructions on how to provide details. She saves the reply in an Outlook folder called “New Servers” to track her work and avoids committing to a timeline in case something comes up. Connie begins by looking at memory utilization on each host and picking the least used, likewise with storage. She distrusts templates and likes to build a new server with her preferred configuration from scratch. When finished, she emails the details to the requestor by copying a previous message of the same type and replacing the changed items.

- Fred has yet another process, and so does Alice.

Unfortunately, other departments at the company are often frustrated and confused by the inconsistent results from Snowflake IT. They have a hard time planning projects with reliable timelines and spend days going back and forth clarifying special cases. They sometimes wonder wistfully: might there be a better way?

The Value of Standardized Processes and Systems

The problem, of course, is that there is no common way of doing things at Snowflake. They have no clearly-defined method for doing even the things that are regularly done, relying instead on improvisation and habit. If you asked the staff how a new server comes to be, they each answer differently. The result is inconsistency, inefficiency, and frustration brought on by needless complexity.

There is no way to move beyond this mode of operation without standards. Not standards in the sense of beer or relationships, but standards in the sense of something defined and consistent. For our purposes, a standard can be defined as:

Standard: a well-defined approach established by common consent within an organization.

Breaking this down a bit, a standard is:

- Written down: If you can’t literally describe it on paper, then it’s not defined. When asking for the standard, the answer should be in the form of a document. It should not be in the form of tribal knowledge.

- Established: the organization stands behind it. It is understood as “the way things are done around here”.

- Of common consent: the people in an organization actually commit to adhering to the standard. If something is written down and nominally established and then ignored, it isn’t a standard.

There is plenty written on standardization, a concept with a rich history dating back to 1800 or so. You might ask, isn’t this old hat after 200 years? The answer is no, unfortunately. Everyone seems to know about it, but most of us don’t practice it consistently, including those working in companies with billions of revenue. Manufacturing has figured it out pretty well, but most other organizations still have work to do, including in the IT department.

What Does This Have to Do with IT Automation?

So far, we’ve said nothing about automation, only about the way people do things in an organization. Emphasizing standards is important for any business, regardless of whether they pursue automation. One compelling argument for this view is the subject of Work the System.

However, standardization has particular relevance to automation, because IT automation is a computer implementation of a standardized process. Put differently, only standardized processes can be automated. Remember that computers are dumb and lack creativity, and do only what they’re told. Therefore, we have to know exactly what we want them to do before they can do it.

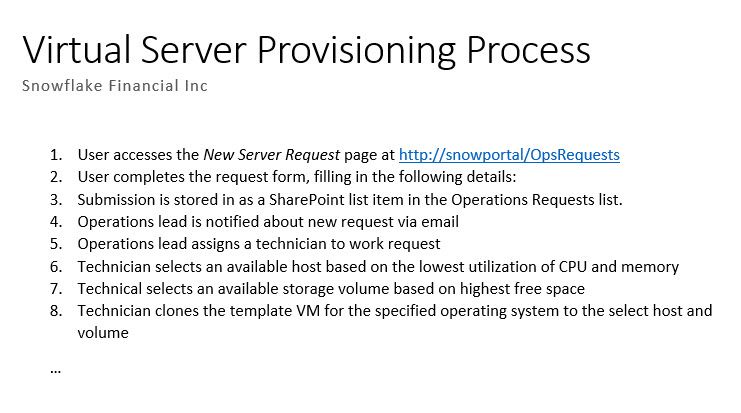

This is why standardizing processes is a necessary first step in automation projects, which often catches people off guard. Revisiting our friends at Snowflake, suppose the boss asks the team to better automate the server provisioning process. They eagerly research and purchase a new workflow automation solution, and sit down to set up their fancy new software.

Then, the arguments begin. How does the request get into the system to start the automated build? Jim suggests people call IT and describe the request, which is entered by the technician into the application console, starting the job. Connie’s idea is for an email to be sent to the system, which will read a template Word document for the necessary information. Fred, the SharePoint admin, thinks a new form on the internal portal should be provided. And where to place the new server being created? Fred goes by workload type, Connie goes by utilization. Many other questions and debates follow. Who is right? What’s the standard?

These questions need to be settled for the project to succeed. With whiteboards, meetings, or other methods, standards must be determined, established, written down, and consented to. Once this non-trivial work is done, the technical portion of the project can more safely proceed with less risk of the implementation being later vetoed by a member of the team who has a different idea about how things should work.

What to Standardize?

There are several important types of things to document when it comes to IT automation. These are: inputs, outputs, data, and process.

Manufacturing is a good physical analog. Materials and orders come into the factory (inputs), they are manipulated in a series of steps (process), parts and components are created that fit together (data), with a new widget shipped out the other end (output).

Processes

A process is a fancy word for a sequence of tasks, stuff that happens in a certain order. In a factory this is visible as a conveyor belt or production line, but in an IT department you see only a bunch of people staring at computer screens. Therefore, it’s critical to write down the steps of a process for it to be made tangible and understood. This doesn’t have to be sophisticated and can be as simple as a numbered list.

The goal is to have a clear, unambiguous list of steps that can be understood by somebody reading it who may not necessarily know the inner workings of the system. In other words, we don’t want a step to contain implications that a smart person in the field would just happen to know, like “everyone knows you need at least two virtual CPUs when creating a database VM”. All such assumptions should be in writing and explained to the reader.

Those with a childhood may have played The Peanut Butter and Jelly Game, which challenges participants to clearly and explicitly explain to somebody how to make a PBJ sandwich, who must then follow their exact instructions. When assumptions are made or instructions poorly explained, hilarity ensues. Entertainment value aside, it’s an excellent way to think about documenting process: if the reader can perform the task by adhering to the letter and without improvising, you’re in good shape. Call it the PBJ Rule of Process Automation.

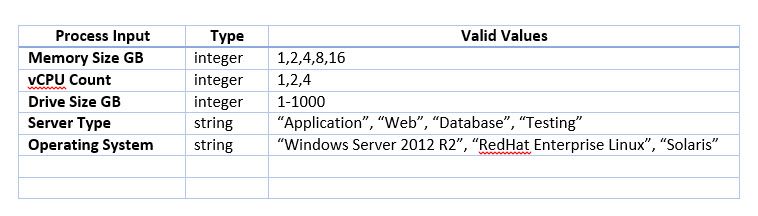

Inputs

IT and business processes have inputs, just not as visibly as factories. Our inputs are pieces of information, namely anything that must be known for the process to start, proceed, and finish. This often takes shape as a request form on a webpage, but can also involve other systems, e.g. the current monitoring readings of virtualization host status.

For standardization and automation purposes, the important thing is that these inputs be known, defined, and written down. This becomes the basis of implementing parameters and integration points in the automated workflow.

Outputs

It’s also important to define what is produced by a process. For one thing, it’s good manners to tell people what to expect when they ask for something. When it comes to automation, this becomes especially useful when chaining multiple workflows together – where the output of one process becomes the input to another.

For example, you might define the specifications for each type of virtual server that can be provisioned, or define a list of resulting accounts and applied configurations for the new employee onboarding process.

Data

Data is the glue the holds an automated process together, and gains more importance as complexity grows. Data includes not only the information provided as inputs and produced as output, but also information used internally during an automated workflow for things like doing calculations, performing lookups, evaluating conditions for decision branches, and more.

The relevant aspect when standardizing for automation purposes is format. The structure, syntax, and semantics of ones and zeros is important because a computer isn’t intuitive enough to know that “SNOWFLAKE\fred” and “fred@snowflakeinc.com” refer to the same person, or that “10.100.1.0/24” and “10.100.1.0 255.255.255.0” refer to the same network. Standardizing data formats means establishing and documenting the way various pieces of information will be stored, consumed, and produced.

Closing Thoughts

The benefits of process standardization are well-established, yet it is often resisted. “Follow the process” is the butt of many corporate jokes, often for good reason: applied without thought and outside of the context of its purpose, all process does is restrict people from being creative and enjoying themselves, which is bad.

Standards need to be applied carefully and always with the purpose of simplifying the mundane to make way for the creative. To paraphrase George Washington, standardized processes are, like fire, a troublesome servant and a fearful master. So, use them wisely.

**

Follow the standard process to share your thoughts in the comments below.